Behind the Scenes 1938: Two Short Films

- Adam Williams

- Feb 23, 2024

- 6 min read

Here are two reviews of short films from 1938, both about filmmaking and the illusory nature of the movies. One might be more informative; one might be more titillating. This will depend on what you already know and what turns you on. Maybe this upstanding Czech film has more in common with this grungy American film than immediately apparent.

At the very least, they’re both worth writing about.

Továrna na iluse (1938, 10 minutes and 36 seconds)

If you ever wanted to know how films were made in Czechoslovakia in the late 30s, this is the film for you. Our droll narrator begins the proceedings quite strangely by explaining he is being shown in negative so that he won’t be recognized. Our anonymous host takes us to the film sets where rustic villages are merely a series of façades meant to be photographed from one angle only. Studio hands demonstrate massive cranes. Workers relax in rickshaws in a phony Chinese village. Films like Svět patří nám and Duvivier’s Golem are mentioned for the benefit of those familiar with Czech cinema. For others, the narrator’s description of this movie lot as “…the terminus of memories, an island of forgotten films,” feels especially apt.

We then enter the propman’s cluttered domain. “He must know everything and have everything.” Strange objects abound in this cavernous warehouse—exotic masks, old medicine bottles, a typewriter from 1890, and cats…many cats. The propman is a cat fancier.

We cannot enter the studio until the light outside the door turns off. There is a film being made. Hugo Haas is directing Bílá nemoc (The White Disease) just a couple years before he emigrated to the States for the next chapter of his career. The director, who also stars in the film, is on top of the world, sitting on a crane in costume next to the Slechta camera (naturally, they’re using a Czech 35mm camera). The massive studio is replete with lights, strewn with cables, and packed with technicians and extras. In the midst of this chaotic scene, we focus on one worker: the clapper.

The narrator asks, “So what is this clapper business all about?”

We find out that it’s a complex business at the heart of synchronized sound. The soundtrack film must be unspooled to understand, and for that we must explore the film laboratory. But you cannot because the film is developed in darkness. “You can see that you can’t see a thing in here,” the narrator-cum-mad-hatter says over a black screen.

We resume our journey when the film is dry. A technician in white coat punches a hole in the film on the frame where the two boards meet to make the clap (look closely at the GIF above), and likewise next to the cluster of white lines on the soundtrack.

The work becomes more microscopic with solitary men hunched over complex instruments.

A positive print is made.

The film is assembled in the editing room.

Then the negative must be cut in accordance with the work print.

“Now you have an idea how much work is required to make a film.”

Movies about the technical aspects of filmmaking in the studio era are few and far between, so Továrna na iluse, which translates to something like The Illusion Factory, is extremely valuable. Its breakneck pacing is playfully contrasted with its lapses into poetry and off-kilter humor. As such, it’s entirely watchable for both luddites and tech geeks. For comparison, watch the 1940 American film The Alchemist in Hollywood. While equally informative, the narrators in this film are as compelling as a group of high school chemistry teachers, and the discussion of film at a molecular level drags on far past the average person’s breaking point.

Now we turn our attention from “behind the scenes” to scenes of behinds…

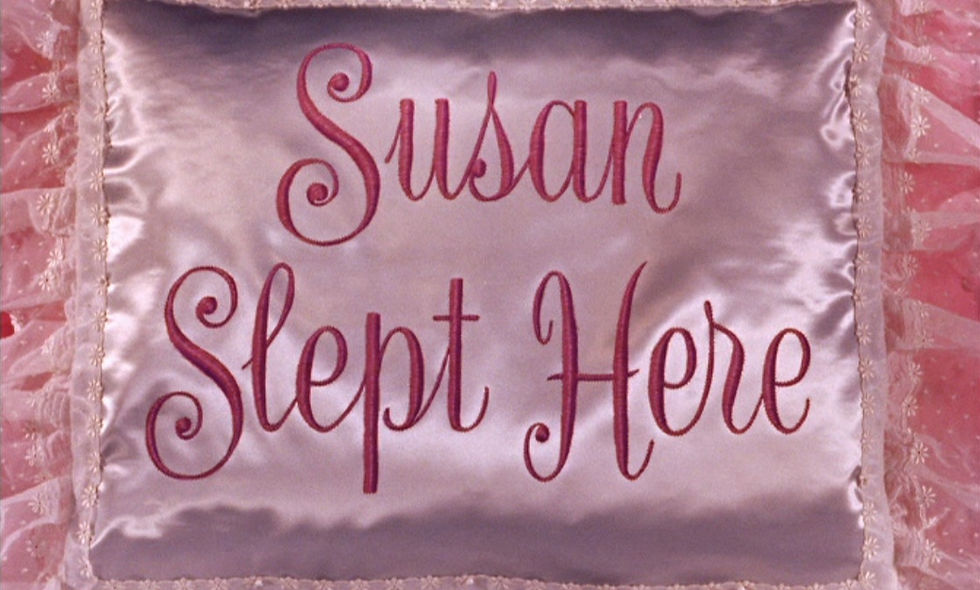

Hollywood Script Girl (1938, 5 minutes and 28 seconds)

There are no credits on this brief picture, as that would be tantamount to a written confession. All the information about this film is contained on the title card. Some company called “Pacific Cine Films” presents it. The subtitle reads, “A Hollywood Art Featurette.” The copyright is 1938.

For those that have not been debriefed on the code words, in particular “Art Film,” let this advertisement from a 1938 issue of Film Fun basically spell it out:

“Beautiful models in action for Art classes and students.” Yeah, right. This film, like all these so-called “Art” films, fulfills man’s basest desire, which is not, as the distributors might claim, to paint classical studies of the human female form. In fact, besides being a home-entertainment staple, Hollywood Script Girl is an example of a “square-up” film that would be shown to satiate the ravenous desire of an audience lured in by hucksters with a program with more sizzle than steak. In his book Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!: A History of Exploitation Films, 1919-1959, Eric Schaefer explains, “Such reels should not be confused with hardcore stag films, as they lacked explicit sexual activity. Needless to say, a square-up reel was not a regular part of an exploitation show and would not be advertised, but it could be used if an audience became unruly and complained that they had not received the spectacle promised by posters and trailers.”

This silent film with intertitles opens with nude girls lounging on a film set when a nervous director loses his cool. His star, Gloria Golden, is nowhere to be found so he orders the script girl to locate her. The mousey bespectacled script girl searches the dressing room (populated with more naked girls, naturally) to no avail. The script girl confides to a friendly chorus girl that she wishes she could be a model. The other chorus girls, who are mean, overhear this confession, strip her, and give her a new wardrobe: a turkey headdress along with a brasserie of two gobblers. The script girl does a little shimmy, letting those turkey wattles wiggle. The friendly chorus girl disperses the crowd and removes the ridiculous costume from the script girl. She then enlists the make-up man to give her a makeover. Now beautified and de-spectacled, the script girl is rushed onto the film set, a Busby Berkeley-esque tinselly staircase fantasia where our ugly duckling unveils herself as a swan to the shock and dismay of the nasty chorus girls.

On the 86th anniversary of Hollywood Script Girl, with the entire cast most assuredly deceased, the film seems more cute than criminal. According to the standards of the day, the film posed a moral threat. In 1943, the feds raided a Philadelphia “film ring” and subsequently arrested four Californians for distributing obscene material through the mail—of which Hollywood Script Girl was one catalog title. William H. Horsley of Associated Hollywood Films, Inc., O.B. Hertwig of Candid Cinema Corp., Robert I. Lee of Pacific Cine Films, and T.H. Emmett, who worked for a film laboratory, were all charged. Later, it was reported that three cameramen who worked on these films—W. Merle Connell, W.E. Grogan, and, again, Robert I. Lee—were sentenced and fined for filming the pictures.

In 1944, The Banner Theatre in Los Angeles got a visit from the vice squad for showing Hollywood Script Girl along with the bluntly titled Nudism.

It almost goes without saying that the details of this production—including the names of the performers and where they filmed it—are undocumented. There is, however, one tantalizing clue. In a high angle shot of the film studio, the 35mm camera is spun around revealing it to be the property of Grand National Pictures, which in 1938 had merged with E.W. Hammons’ Educational Pictures. This does look to be filmed in a functional studio space, so it’s not too much of a leap to assume this movie was an unauthorized production by studio technicians. (I can’t help but imagining the security being placated with a bottle of booze and, perhaps, a smile and wink from one of the chorus girls.)

The film is surprisingly well-lit and staged, which gives credence to the theory that it was made by people who made legitimate films for a living.

As brisk as a pop song, Hollywood Script Girl does the most with its runtime delivering a complete story arc and an eye-searing amount of skin. It’s perfect for your next smoker, just keep it on the hush hush.

Comments